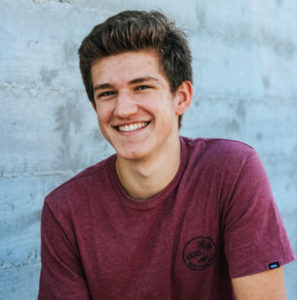

It was the kind of innocuous interaction that happens on countless college campuses on any given Friday night. A neighbor knocked on the dorm room door of Elisheva Engel (Film/Video BFA 20)and asked her if she wanted to go to a party off campus. For Engel, who had arrived at CalArts only weeks earlier from the Orthodox Jewish community on Long Island where she grew up, the question was hardly trivial.

Getting to the party would involve a car ride, which would mean that Engel would be breaking Shabbat—something that was strictly prohibited back home. “The last time I was in a car on a Friday night I was in my mother’s womb on the way to the hospital,” Engel joked. But the film student was determined to fully embrace everything that was different about her new community so she decided to go to the party.

It was liberating beyond her wildest dreams.

“The other people who were there with me weren’t really aware of what was happening inside my head,” Engel said. “But the experience allowed me to be free. For the first time, there was nobody there to judge me and tell me that what I was doing was wrong.”

Despite her upbringing in an Othodox community, isolated from nearly anything secular, Engel’s parents offered her a glimmer of a different world. Her mother was artistic and her father—the son of Auschwitz survivors—had a particular soft spot for films and often took his children to see movies. That experience led to Engel’s own love of film and she could often be found capturing life around her from the camera on her phone. Filming her community gave Engel a more detached perspective of it, one that helped to nurture a long-held sense of unease that she had with its more dogmatic elements.

Engel’s decision to attend CalArts was based largely on how different it was to what she had been used to. It was an institution that valued openness, experimentation, critical engagement, and creative freedom, and Engel was anxious to find out if such an environment would help her grow as an artist. Her decision was supported (with a bit of hesitancy) by her parents but given her family’s modest means, it was a financial burden that was not feasible without assistance. CalArts was able to award her a scholarship, derived from general funds provided through philanthropic support. The scholarship covered about half of Engel’s tuition costs, reducing some of the financial burden and allowing her to focus more fully on her filmmaking.

For Engel, being surrounded by other student-artists who were passionate about film and art was inspiring. And the fact that faculty at CalArts encouraged exploration as part of the students’ artistic practice—helping them find their purpose as artists—was a revelation. Engel cites faculty member Cauleen Smith as a catalyst for shaping her artistic goals during her first year at the Institute. The death of Engel’s father at the end of her first year helped to give her filmmaking even greater purpose. Her father’s passing precipitated a stint as an exchange student at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem. Engel’s experience in the ancient city helped to further propel the spiritual evolution that she had begun at CalArts. It was also where she filmed some of the key footage for her documentary, Shabbosdik (a Yiddish word that roughly translates to “Sabbath-esq”). Engel also received an Allan Sekula Social Documentary Award from CalArts to help support its production.

“What excited me about being in Jerusalem was that it expanded my view on who and what a Jew could be,” Engel said. Seeing pluralistic versions of Judaism across the city helped her recognize that the Jewish experience didn’t have to be as communal as she was used to it being; it could be personal and individualistic. That realization is the narrative thread that runs through Shabossdic, which Engel has nearly completed. The film is a deeply personal—and sometimes uncomfortable—examination of Jewish identity. “I’m kind of pouring my heart out in this film,” Engel said.

As she remembers the advice that CalArts faculty member Cauleen Smith gave to her about finding purpose in her work, Engel sees Shabbosdik in a hopeful light. “I feel like I’m making the film for the Orthodox Jewish community that I left,” she said. “In part because I want to explain myself to them, but also, if I can speak to one person who might be feeling what I was feeling, then I’ll have achieved my goal as a filmmaker.”